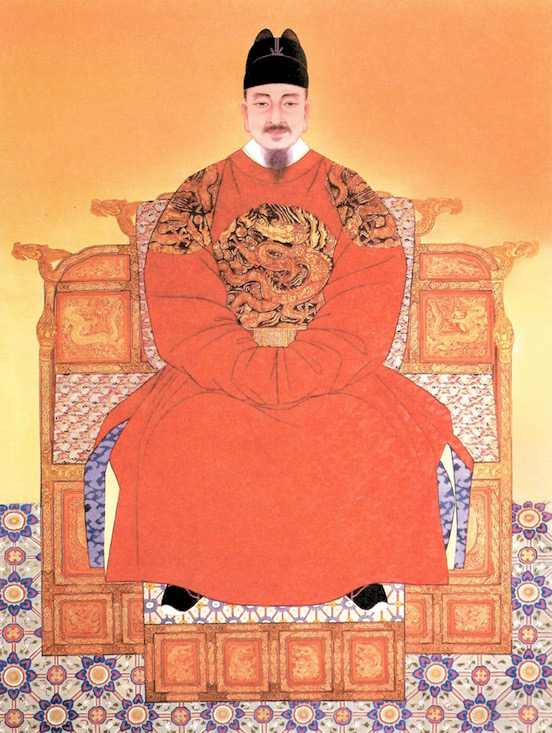

King Sejong the Great

The most enlightened ruler in Korean history

Among all the great Korean historical figures, the most famous is probably Yi Do (이도), best known as Sejong the Great (세종대왕), fourth king of the Joseon dynasty. Despite having ruled more than five centuries ago, Sejong is still remembered today as the most enlightened ruler in Korean history.

Sitting in the middle of Gwanghwamun Plaza (광화문광장) in central Seoul, his 9.5-meter high statue is an important touristic landmark. His face is also part of daily life in South Korea as it is printed on ten thousand won bills (about ten US dollars). The country went as far as naming its new administrative capital Sejong Metropolitan Autonomous City (세종특별자치시).

So who was this great king? And what did he do to deserve such honors?

Creation of the Hall of Worthies

Born in 1397, Sejong was the third son of King Taejong. As such, he was not first in line to succeed to the throne. But as he excelled in his studies, while his older brothers did not, Taejong ended up putting him on the throne anyway, despite the opposition of his ministers. Sejong thus became king in 1418, and reigned for thirty two years until he died of sickness in 1450.

As a young prince, Sejong was an avid reader and a diligent student. Even after he ascended to the throne, his eagerness to learn led him to study such advanced topics that teaching the King became a full time job. Aware of the value of surrounding himself with smart people, Sejong ordered in 1420 the creation of a research institute within the palace. This institute was named Jiphyeonjeon (집현전), or Hall of Worthies, and hosted the country's twenty or so top scholars. Their duties were to administer the King's education, grow the royal library by publishing books, and complete research assignments to help Sejong carry out his reforms.

Reform of the Land Tax

One such reform intended to make the land tax fairer for farmers and more effective for the state. At the time, farmers had to give ten percent of their harvest to the government every year, but tax inspectors were supposed to gauge the quality of the harvest and adjust the tax rate accordingly. Of course this system led to corruption: farmers would end up paying too much taxes and the government's revenue would dwindle while tax inspectors enriched themselves.

Sejong initially proposed that this system be replaced with a flat nationwide tax rate based on the average of the harvests of the previous years. The main concern with this proposal was that it would be unfair to farmers living in less fertile regions. Therefore, the proposal was amended to take into account the fertility of each region.

It took more than twenty years for this reform to be finalized. Sejong could have pushed it through much faster, but instead he started by surveying the opinion of 170,000 of his citizens, from farmers to court officials. He then organized debates to improve the law based on the findings of the survey. Finally, he experimented with this new law in the Cholla province before spreading it to the rest of the country. This rigorous process shows how concerned Sejong was about the fairness and the practicality of his ideas.

Invention of the Korean Alphabet

The reform of the land tax is one example of the many ambitious projects Sejong carried out with the help of the Jiphyeonjeon scholars, but his most enduring legacy is certainly the creation of Hangul (한글), the Korean alphabet.

Sejong was convinced that the main role of a king was to make his people happy, and that education was the key to improve people's lives. In order to educate themselves, people needed to learn how to read and write. That meant memorizing thousands of Hanja (한자), the Chinese characters used at the time, a feat that was out of reach for common people. The fact that Chinese characters were inadapted to the complex Korean grammar only made their use more difficult.

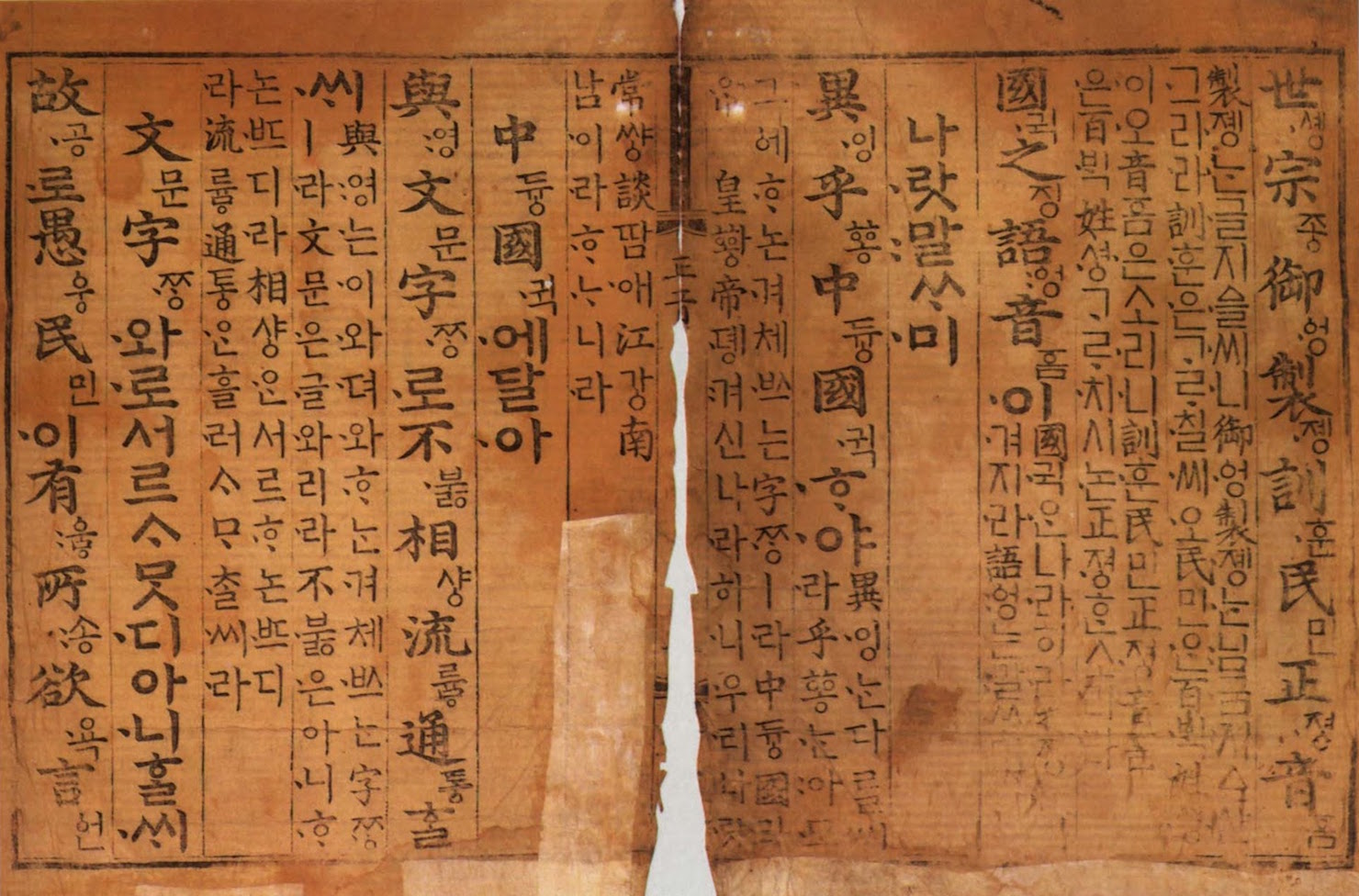

To overcome this obstacle, Sejong set out to design a new writing system specifically for the Korean language, with the constraint that common men and women should be able to learn its usage easily. The twenty-eight letters that formed the original Hangul were created in 1443, and publicly unveiled in 1446 in a document titled Hunmin Jeongeum (훈민정음, The Proper Sounds for the Instruction of the People).

The preface, written by the King himself, states:

The spoken language of our country is different from that of China and does not suit the Chinese characters. Therefore amongst uneducated people there have been many who, having something they wish to put into words, have been unable to express their feelings in writing. I am greatly distressed because of this, and so I have made twenty-eight new letters. Let everyone practice them at their ease, and adapt them to their daily use.

The letters were indeed simple to learn for anyone, yet able to express all Korean sounds. But despite its intrinsic qualities, Hangul triggered a firm opposition from the establishment. For officials in power, teaching common folks how to read and write was a dangerous idea. And for scholars who spent their lives studying Chinese writings, using a native alphabet instead of Chinese characters, as did the Mongols, was seen as barbaric. For these reasons, Hangul did not reach mainstream usage until the middle of the 20th century.

Nowadays, Hangul has mostly replaced Chinese characters both in North and South Korea, and the date of its publication is celebrated as a national holiday (Hangul Day). Simple letters for the people, along with other progressive ideas such as paternity leaves or the right to appeal a judge's decision, show that King Sejong was a visionary leader that cared more for the well-being of its people than the privileges of the ruling class. He is still a great source a pride for many Koreans today.